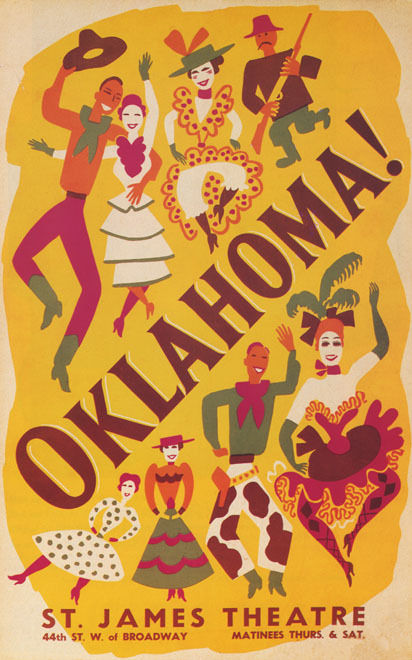

Today we present the first in a three-part series on the 75th anniversary of Oklahoma!, probably the most important musical in Broadway history, which made its debut at the St. James Theatre in New York on March 31, 1943. We will discuss the origins of the show, a look at its predecessor, the play Green Grow the Lilacs, and how the musical version not only launched the careers of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein as a team, but also revolutionized how musical theater was written and produced.

The history of musical theater can be divided into two eras: shows that existed before Oklahoma! and shows that came after it. It’s rare that so much importance can be bestowed on any single show in Broadway history, but if there ever was one, Oklahoma! is it. One would have to go back in time to March 31, 1943 when the show made its debut to understand exactly how startlingly different Oklahoma! was in its day.

The 1942-43 musical season was sparse when it came to new book musicals. Only five were introduced that season, of which two were hits. The rest of the season consisted of a mixture of vaudeville-styled revues and revivals of older shows. One was This Is the Army, a revue written around the songs of Irving Berlin. The show lasted only 113 performances, but every performance was sold out. Another, Ira Gershwin and Kurt Weill’s Lady in the Dark, was already going through its second revival, with star Gertrude Lawrence reprising her role as Liza Elliott.

Other than Oklahoma!, the only other show of note that made its debut that season was Something for the Boys, a splashy Mike Todd production starring Ethel Merman and featuring a score of Cole Porter songs. The show was really nothing more than a breezy story with music that was typical of other light-hearted Porter shows like Anything Goes. So when Oklahoma! made its debut on the last day of March, it appeared at a time when Broadway was wide open for something new and inventive.

Oklahoma! had everything going against it when it appeared on the Broadway scene after playing to lackluster results in New Haven, Connecticut. It was based on a rustic folk-play, Green Grow the Lilacs that only survived for sixty-four performances when it ran in 1931. Its composer, Richard Rodgers, who had for years been writing shows with his partner, Lorenz Hart, was breaking in a new lyricist, Oscar Hammerstein II, who hadn’t had a hit show since the 1930s. There were no stars in the cast to combat the celebrity of La Merman, who was playing down the block. Choreographer Agnes de Mille had never worked on a musical comedy before, and producer Rouben Mamoulian’s only claim to fame was Porgy and Bess, a groundbreaking show, but a financial flop. Financial backers were hard to find in 1943; the Theatre Guild was running low on cash and reportedly only had $30,000 in the bank.

But despite all of these negative signs, Oklahoma! become a rousing success, revolutionizing Broadway forever. It was not just the first musical since Show Boat (1927) to tell a serious story and integrate its songs into the plot, but it also included a ballet, something Rodgers had experimented with before in On Your Toes (1936) with “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue.”

Comparing Oklahoma! with Something for the Boys is the perfect way to understand the instant maturing of musical comedy. Something for the Boys was a throwback to the early days of musical theater, when shows were presented like Viennese operettas, lighthearted romps that suspended storylines to introduce songs. Oklahoma! defined a new, specifically American style of musical, one that required its songs to define characters and further the plot. Furthermore, it targeted not just the nouveau-riche theatergoers, but the average American, and was accessible to audiences in the American heartland as well as under the bright lights of Broadway. It was simply nothing like anything that had been seen on an American stage before.

**********************

Tomorrow, we will look at Green Grow the Lilacs, the 1931 play that became the basis for the musical version created by Rodgers and Hammerstein 12 years later.

No Comments