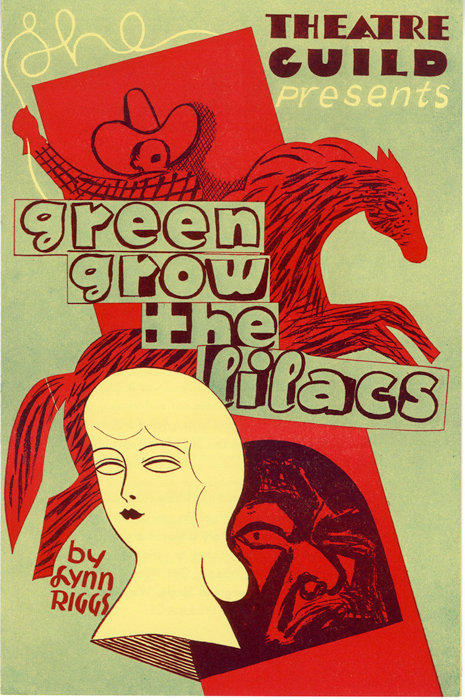

LYNN RIGGS AND GREEN GROW THE LILACS

Oklahoma! would not have existed without Green Grow the Lilacs, a lively tale of life on the American prairie, set in 1900 when Oklahoma was still Indian territory. (It wouldn’t become a state until 1907). It was here where playwright Lynn Riggs was born, in 1899. Riggs’ father was a rancher and banker who lived with his wife, a woman of Cherokee Indian descent, on a ranch near Claremore, ten miles from Oologah, the birthplace of cowboy philosopher Will Rogers.

Riggs got his early education at the Eastern University Preparatory School in Claremore, but left home at seventeen. When he returned, he attended college at the University of Oklahoma, but left before graduating, and moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico. There he began his writing career, writing a one-act play that was staged in 1924. His first major play, Big Lake, was produced in New York in 1926. Other plays followed, all of which were drawn from Riggs’ memories growing up on the Oklahoma plains.

In 1928, while traveling through Europe on a Guggenheim scholarship, Riggs began work on Green Grow the Lilacs. The show’s title was based on an American folk song whose roots go back to a traditional Scottish ballad titled “Green Grows the Laurel.”

Green grows the laurel and sweet falls the dew

Sorry was I love when parting from you

But by our next meeting I hope you’ll prove true

And we’ll change the green laurel to the violets so blue

Folk songs and ballads played a huge part in Riggs’ play. The memories of growing up with these songs are what spurred Riggs’ simple tale of a naïve young girl named Laurey who was being brought up by her Aunt Eller after her parents’ death. Laurey is torn between playing hard-to-get with the handsome cowboy Curly and fending off the advances of brutish ranch hand Jeeter Fry.

In the introduction to his play, Riggs said that the intent of the play was to “recapture in a kind of nostalgic glow the great range of mood which characterized the old folk songs and ballads I used to hear in my Oklahoma childhood—their quaintness, their sadness, their robustness, their simplicity, their melodrama, their touching sweetness.” Indeed, at key moments in the play, the main characters break into song to illustrate their feelings at the time. Green Grow the Lilacs was not a musical, but music played a big part in its story and the effect it would have on its audiences.

THE SONGS

The play is constructed in six scenes; the first three of which are used to define and amplify the characters, with the major action of the play following in the succeeding three scenes. Some of the songs are performed by the characters as indicated in the play, while others are sung by members of the ensemble at points not indicated in the script. The songs included in the play are:

“Whoopee Ti-Yi-Ay, Git Along, You Little Dogies” (Curly)

“A-Ridin’ Ole Paint” (Curly)

“Green Grow the Lilacs” (Curly)

“The Miner Boy” (Laurey)

“Sing Down, Hidery Down” (Aunt Eller)

“Sam Hall” (Curly)

“The Little Brass Wagon” (Ensemble)

“Custer’s Last Charge” (Old Man Peck)

“And Yet I Love Her Till I Die” (Curly)

“My Lover’s Gone Off on a Train” (Ado Annie)

“Skip to My Lou” (Ensemble)

The play indicates additional folk songs were to be sung during the production, although they are not indicated in the script itself. These songs include “Hello, Girls,” “I Wish I Was Single Again,” “Home on the Range,” “Goodbye, Old Paint,” “Strawberry Roan,” “Blood on the Saddle,” “Chisholm Trail,” and “Next Big River.”

THE CAST

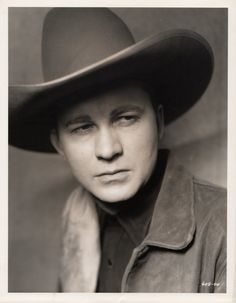

The show starred twenty-four-year-old Franchot Tone (1905-1968) as Curly. Tone, who, despite having appeared in nine previous plays dating back to 1927, was singing for the first time. Laurey was played by June Walker (1904-1966), a theater veteran at the age of twenty-six, having played her first role when she was just fourteen. Another irony that links Green Grow the Lilacs to Oklahoma! is that Walker’s son, John Kerr, played the role of Lieutenant Cable in the film version of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific in 1957.

Theatre Guild board member Helen Westley (1875-1942) played the key role of Aunt Eller Murphy. Westley also appeared in the play Liliom, which became the inspiration for Rodgers and Hammerstein’s next musical, Carousel, in 1945. It is Aunt Eller who gives the most impassioned speech in the play, one that would anticipate a similar speech by Ma Joad in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath nearly ten years later. In the play, Aunt Eller is talking to Laurey about the death of Laurey’s father Jack, her husband, who died tragically after getting hit by a stray bullet. Without self-pity, Aunt Eller sums up the defiant, can-do spirit of the Oklahoma settlers when she says:

All I knowed was, my husband was dead. Oh, lots of things happens to a woman—sickness, bein’ pore and hungry even, bein’ left alone in yer old age, bein’ afraid to die—it all adds up. That’s the way life is—cradle to grave. And you c’n stand it. They’s one way. You got to be hearty. You GOT to be.

Four of the folk songs were sung by Maurice Woodward “Tex” Ritter (1905-1974), who played rancher Cord Elam in the show. Ritter, a 25-year-old Texan who had been educated at the University of Texas in Austin, had been performing on Broadway since 1928, when he sang in the men’s chorus for the musical The New Moon, whose book and lyrics were written by, ironically, Oscar Hammerstein.

The cast of Green Grow the Lilacs also included future acting mentor Lee Strasberg (1901-1982), who played the role of the Pedler. Operatic baritone Richard Hale (1892-1981) appeared as Jeeter Fry; Hale would later play Dr. Brooks in the 1943 revival of Lady in the Dark.

THE STORY

Oklahoma! follows the story of Green Grow the Lilacs fairly closely. Curly, Laurey, and Aunt Eller remain the same as they were in the original play, however, Jud Fry’s name was original Jeeter Fry. In the original play, Ado Annie is described as “unattractive” and “stupid-looking,” with taffy-colored hair pulled back from a freckled face. Her character would become more attractive and flirtatious in Oklahoma! and was given a comic song, “I Cain’t Say No.” Ado Annie’s beau in Oklahoma!, Will Parker, is mentioned in the mentioned in the smoke-house scene as being a Claremore boy who can spin a rope and chew gum at the same time, but the character never appears in the play. The subplot romance between Ado Annie and Will Parker was created for the Rodgers and Hammerstein production. Other cast changes included “the Pedler” being given the name of Ali Hakim and the additions of the characters Gertie Cummings and Andrew Carnes (The Carnes character is comparable to Old Man Peck in Green Grow the Lilacs).

The ending of Green Grow the Lilacs also differs from that of Oklahoma!,albeit only slightly. In the original play, Curly is arrested after Jeeter Fry’s accidental stabbing during the shivaree, but escapes from jail to spend his honeymoon night with Laurey. When the sheriff and the townsfolk appear at their house to get him to surrender, Curly pleads with them to let him have one evening with Laurey before his hearing. The play ends with Curly singing “Green Grow the Lilacs” to Laurey from their bedroom window. The idea of the impending statehood campaign for Oklahoma is never mentioned in the play.

Here is Tex Ritter’s 1945 recording of “Green Grow the Lilacs”

Green Grow the Lilacs ran for only sixty-four performances, from January 26 to March 21, 1931. Despite its lack of success, the play earned the praise of New York Times theater critic Brooks Atkinson, who called it “a sunny part of the American legend.” It would languish in peoples’ memories for another decade before Richard Rodgers decided to make it the launching point for a new stage in his career as a Broadway composer.

Tomorrow, we will talk about the changes Rodgers and Hammerstein made to Green Grow the Lilacs and how they developed their memorable score, as well as the invaluable addition of Agnes de Mille’s choreography. We’ll also look at how the Broadway production helped save the struggling Theatre Guild from going under.

No Comments