RODGERS & HART BECOMES RODGERS & HAMMERSTEIN

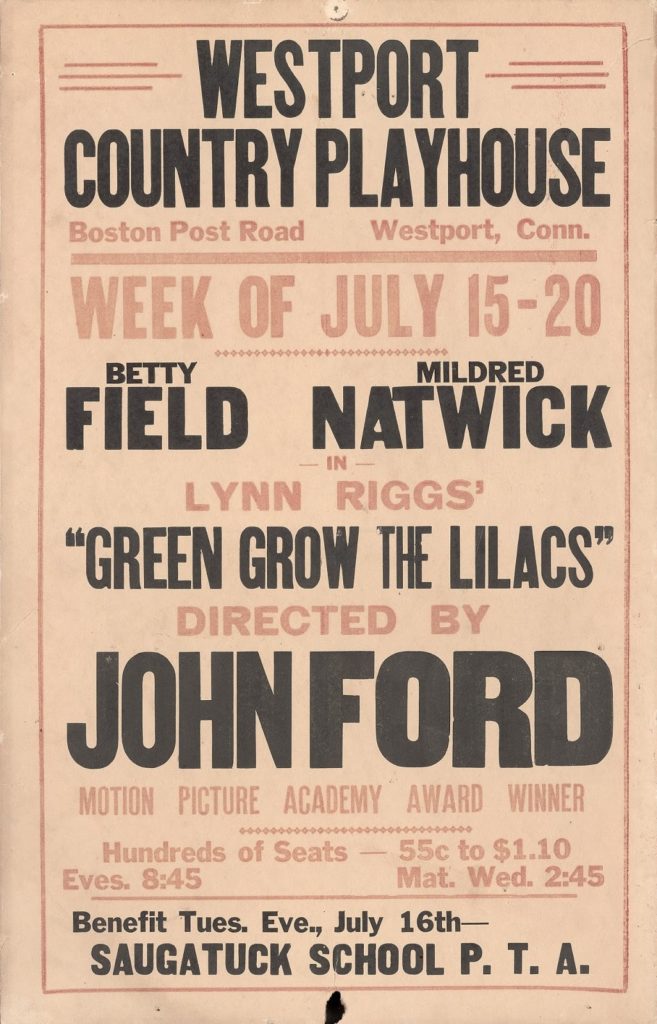

In July 1940, Theatre Guild’s Lawrence Langner invited his Connecticut neighbor Richard Rodgers to see a revival of Green Grow the Lilacs at the Westport Country Playhouse. Famed film director John Ford was scheduled to direct, with John Wayne cast as Curly, although neither Wayne nor Ford showed up for the production. (Ford was ultimately listed as producer.) Replacing Wayne was another Ford protégé, Ward Bond, while the choreography was handled by a talented young actor/dancer named Gene Kelly. Kelly would be tabbed to star in Rodgers and Hart’s forthcoming show, Pal Joey, which opened on Broadway that Christmas. Also in the cast were Betty Field as Laurey and Mildred Natwick as Aunt Eller.

By 1942, Theatre Guild was teetering towards bankruptcy and thought that a Rodgers and Hart musical might save the day. Langner and the Guild’s Theresa Helburn once again brought up Green Grow the Lilacs, and Rodgers thought it was a splendid idea. The show was different from anything else he had done and he thought that the story was ripe for his kind of songwriting. Rodgers and Hart’s most recent production, By Jupiter, had made its Broadway debut in June, on its way to a successful year’s worth of shows, but by August, the partnership was falling apart, due to Hart’s increasing depression and alcoholism. Rodgers made one last attempt to convince Hart to join him in the project, but Hart did not think much of the play, nor was he in any shape to work anymore. Saddened at his partner’s condition, Rodgers turned to his friend Oscar Hammerstein, who agreed to write the libretto and the lyrics.

WRITING THE SCORE

After weeks of discussion, Rodgers and Hammerstein were faced with an array of problems that needed addressing. First, they had to ensure that the charm of Green Grow the Lilacs could survive the excising of all of the folk songs that inspired Lynn Riggs to write the play in the first place. The new score had to fit the time and location depicted. Both Rodgers and Hammerstein understood this at the outset, their first big problem: how to open the show. It’s hard to understand today, but in 1942, most musicals opened with an opulent chorus line, featuring a bevy of brightly costumed girls. Rodgers and Hammerstein decided to leave the show the way Riggs had written it, with Aunt Eller on stage by herself and Curly singing a folk song in the wings. Musical comedies never featured a villainous character, much less one getting killed on stage, but they insisted that stay as well, although the character’s name would be changed from Jeeter to Jud.

Most important of all, Rodgers and Hammerstein decided to experiment with an idea they had been thinking of: to ensure that all musical and dance elements in the show were germane to the story. To do this, the lyrics had to be written first, and then a melody ascribed to them. This reversed the roles composers and lyricists had played in Broadway for decades, a practice that Rodgers had followed with Hart, and Hammerstein had followed with his previous partners, Jerome Kern, Rudolf Friml, Sigmund Romberg, and Vincent Youmans. By writing his melodies to Hammerstein’s lyrics, Rodgers’ work took on an entirely different nature. They were not only melodious, but they reflected the personality of the character he was writing them for.

In his book Rodgers and Hammerstein, author Ethan Mordden discussed how Oklahoma! changed the rules of a Broadway show: “Don’t start with a star; start with a story – Don’t paste fun onto the show; find the fun within the action – The songs and dances define the characters or further the narrative.” The idea of Oklahoma! was not to show a New Yorker’s view of what Oklahoma was like at the turn of the century, but to show it from Oklahomans’ point of view, using their language.

The first thing Hammerstein did was address Curly’s opening number. In Green Grow the Lilacs, that song was the cowboy ballad, “Whoopee Ti-Yi-Yo, Git Along, Little Dogies.” Hammerstein was inspired by Riggs’ own lovely stage direction at the outset of his play:

It is a radiant summer morning several years ago, the kind of morning which, enveloping the shapes of earth—men, cattle in a meadow, blades of the young corn, streams—makes them seem to exist now for the first time, their images giving off a visible golden emanation that is partly true and partly a trick of imagination focusing to keep alive a loveliness that may pass away.

Hammerstein started his lyric with “Oh, what a beautiful mornin’,” retaining the dropped “g” in the regional dialect of the area. All of the songs were written in dialect, a device that helped make audiences believe that the songs were actually being created by these characters. Hammerstein included the images of the corn and the golden haze over the meadow, but was careful not to elevate Curly’s language beyond what his character was capable of. “He is, after all,” Hammerstein said later, “just a cowboy, not a playwright.”

The line “the corn is as high as a elephant’s eye” was originally “a cow pony’s eye,” but realized when looking at a neighbor’s cornfield that it would have been higher than that. After three weeks, including a time when Hammerstein struggled with the placement of the word “Oh” in the title, the song was finished. Rodgers saw the line “the corn is as high as a elephant’s eye” and immediately came up with a lilting waltz that took him only ten minutes to write.

Hammerstein’s genius at lyric writing was perfected with that song. He realized that directness and simplicity were the keys to writing for a character, and his job was made easier due to his comfort in writing in a variety of dialects. All the songs in the show were written in this fashion, except for “People Will Say We’re on Love,” a duet in which Curly and Laurey declare their love for each other, but each is too cautious to do it blatantly; instead, there has to be an aspect of antagonism between them, with neither willing to expose his or her true feelings.

THE CHOREOGRAPHY

In addition to the lyrics of the songs, Agnes de Mille’s choreography combined her own techniques in designing dance with traditional dance styles that were prevalent at the time Oklahoma! took place. The musical featured a combination of square dancing, tap dancing, pop dancing, and traditional ballet. De Mille had recently choreographed Aaron Copland’s Rodeo and was well suited to working with corral and ranch house settings, as well as deciding how women saw themselves in a fundamentally masculine environment. De Mille’s choreography worked perfectly into songs such as “Kansas City,” in which Will Parker describes the new kinds of dances he learned while in the big city (“The waltz is through,” he announces, introducing hoofing.) With Oklahoma!, dance became an integral part of the story, rather than something used simply to go along with the action. De Mille’s masterpiece, however, was “Laurey’s Dream Ballet,” in which Laurey imagines herself in the middle of a battle-to-the-death between Curly and Jud. The ballet, which ended Act I, embraced the action and Laurey’s fears better than in any musical that preceded it. Although using dance to tell a story existed before Oklahoma!, De Mille’s work in the show helped firmly establish it – just as Hammerstein had done with his lyrics – once and for all as a prime method of furthering a storyline using dance.

SHAPING OKLAHOMA!

The combination of Rodgers and Hammerstein was perfect for Oklahoma! Rodgers, whose strength was in musical comedy, was in his prime. Hammerstein, however, represented an era that was considered passé by the 1940s, when musicals were still influenced by European operettas, with majestic, passionate lyrics set to Old World melodies by such stalwarts as Jerome Kern and Rudolf Friml. What Hammerstein added to Oklahoma! was not only his ability to flesh out characters with realistic lyrics, but he was also a top-notch librettist, and filled out the spare story from Green Grow the Lilacs with the whimsical subplot romance between Will Parker and Ado Annie. When adding the peddler into the mix, now given the name Ali Hakim, Hammerstein was able to balance one romantic triangle (Curly-Laurey-Jud) with another (Annie-Will-Ali). Romantic subplots, now a staple in musical theater, can also be traced back to Oklahoma!

The other element that Hammerstein added to the story was the concept of Oklahoma’s statehood. In “The Farmer and the Cowman,” Hammerstein reasoned that the two warring factions should get along because someday, the territory would become a state, and its inhabitants must act like brothers in order to succeed.

As successful as the Rodgers and Hart teaming was, it was one-dimensional when compared with what Hammerstein added to the mix: not just wit and lyrical genius, but the ability to capture a character’s heart and soul with his words.No Broadway musical had a greater impact on the entertainment industry than Oklahoma! Its transformation from a quaint, marginally successful play to a major Broadway production showed Rodgers and Hammerstein’s ability to recognize properties that would best suit their new idea of integrating music into a story line.

Initially, the show was called Away We Go!, a title that stuck all the way through the traditional pre-Broadway run in New Haven, Connecticut. A decision was made prior to the show’s opening in New York to rename it “Oklahoma.” The concept of the show’s underlying ambition to celebrate the forthcoming statehood added a literal exclamation mark to the show’s title, to emphasize the forthright, can-do attitude of its residents, as well as the sheer theatricality of the production, warding off any possible assumptions that the show would be about barren barns and pallid prairies.

Oklahoma! was an immediate hit, with patrons clamoring for tickets just as feverishly as those in recent years clamored for Wicked and Hamilton. The show ended up lasting for five years on Broadway, setting a record with 2,212 performances. It has been a constant presence on stages around the world ever since, sparking numerous revivals, world tours, a legendary film version in 1955 starring Gordon McRae and Shirley Jones, and ultimately receiving the Pulitzer Prize.

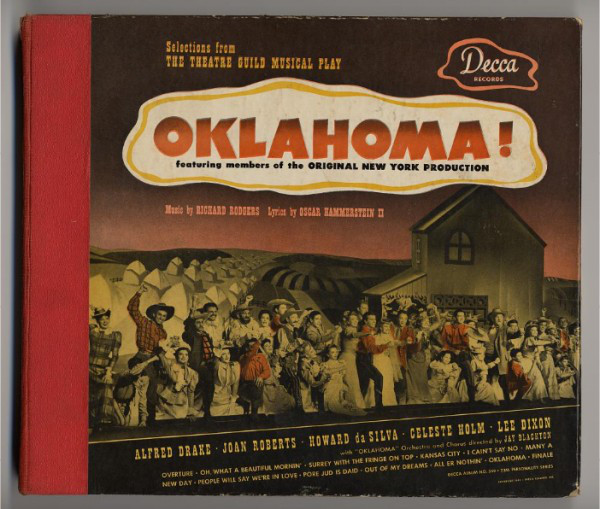

THE CAST ALBUM

In addition to revolutionizing musical theatre, Oklahoma! also put an exclamation mark on the recording industry when Decca Records president Jack Kapp decided to record the show’s songs on a four-disc 78 rpm album. Kapp had been successful the year before when he produced a recorded version of songs from the popular revue This Is the Army, with proceeds going to Army Emergency Relief. That project utilized a studio orchestra and pickup choir, but for Oklahoma! Kapp wanted the original cast. After the show became a hit, the album became a traveling advertisement for Rodgers and Hammerstein’s glorious score. As a result, the cast album became a hit as well, and the habitual recording of songs from hit shows became an industry practice from that point forward. Before that time, individual songs from shows often became more popular than the shows themselves, but with Oklahoma!, the entire score became celebrated as a unique entity on its own.

THE LEGACY

Seventy-five years later, Oklahoma!’s status has only grown. As remarkable a show as it is, one can only imagine the impact it had on theater audiences three quarters of a century ago. What was it like? Well, even though the original production was never visually recorded, a painstakingly produced restoration of the original 1943 production was completed in 2011 by the University of North Carolina’s School of the Arts. Although college students played all the parts, the ages of the characters were probably closer to those of college students than were 28-year-old Alfred Drake and 26-year-old Joan Roberts in the original production. The UNC production is viewable on YouTube in its entirety and is well worth seeing. Click on the links below (it’s in two parts) to enjoy the wonder of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s original production.

No Comments